Policy futures and a politics of care

Ideas of the future and intergenerational fairness in policy design

There’s a diagram used by policy development teams around the world to represent their work to themselves and others: the ‘policy cycle’. This comforting wheel presents policy design as an orderly progression through a number of stages, before coming back round to the start. Policy never sleeps! As the Institute for Government point out in their useful 2011 report, Policy making in the real world, this is a tidy approximation of a process that in reality is a good deal messier, as every civil servant knows. But this abstraction is a way of making policy work graspable.

The ROAMEF policy development cycle, from the HMT Green Book, p. 15

It’s also a way of making foresight manageable, offering clear points where the outputs of futures thinking can be connected with the work of developing and evaluating policy. The biggest practical challenge facing internal policy foresight teams is answering what the late, and much-missed, Cabinet Secretary Jeremy Heywood used to call the “policy ‘so what?’ question”: helping colleagues tasked with developing policy understand what they need to do in the light of foresight work. It’s tempting, faced with that challenge, to try and show how futures work can connect neatly to other ‘tools’ and ’resources’ that are available to policy teams. But what happens to the future when it’s managed in this way?

Hello! I'm Richard Sandford, programme lead for the MSc Heritage Evidence, Foresight and Policy, based in the UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage at The Bartlett. This is newsletter 5 in an increasingly irregular series of 8, giving a flavour of what the programme’s about. Questions? Feedback? Drop me a line.

Foresight has been represented as an essential first step in setting the challenge for policy development, showing teams what the issues are and setting out where we might go. It’s been seen as a source of regular input into the policy cycle, contributing evidence and perspective at different moments. In more recent years it’s been presented as one more technique in the heterogenous glossaries produced by ‘policy labs’, something to be ‘applied’ to a problem alongside other modish constructions like personas, ‘data science’ and hackathons. All of these integrate futures thinking with the other practices of professionalised policy planning. (The UK civil service recognises the use of foresight as a central skill for policy making through its inclusion in the Policy Profession Standards, alongside ‘communicating with influence’ and ‘commercial’ — this is something I am proud to have had a hand in, some years ago).

Domesticating the future in this way, however, leaves some important things unquestioned. Policy teams tend to default to understanding society in a particular way, with talk of ‘policy levers’ and ‘what works’ standing in for an account of how social change happens and what we can know of it. This keeps policy attention on the surface of things, focused on finding ‘solutions’ to specific problems. But such a limited way of understanding social change prevents teams asking questions about how those problems arose in the first place: what underpinning social structures and mechanisms are responsible, and what can we do about those? The rise of behavioural insights and design thinking in government, with their focus on changing how things are perceived by members of the public, rather than on systemic social change, might in part be due to the ease with which they allow these politically-difficult questions to remain unasked (perhaps even making them unaskable). So the future, in practice, turns out to be something that we create through a series of sticking-plaster solutions, gradually tidying the edges of a society that’s seen as basically fine.

Thinking about the future in this way is not going to bring about the change we need—not even the changes we’ve signed up to, like net zero carbon emissions by 2050. But there are other ways of thinking about the future for public policy.

Study of Clouds over the Sound, Eckersberg, C.W (1825-26)

Before I go much further, I ought to emphasise a difference between the way in which design and related practices are imagined within the policy teams I worked with, and the kind of scholarly attention to the relationship between design and policy development that follows on from the critical design stance I described in the last newsletter. There are people working within the field who are deeply thoughtful about exactly the kinds of things I thought were missing from design as policy teams seemed to encounter it. Lucy Kimbell, for example, has been at the heart of explorations of how design, futures, and policy design collide and are being used to develop more inclusive and participatory practice: she’s worked with the UK’s Policy Lab, and her 2017 article with Jocelyn Bailey is a really useful overview of work in this area.

Lots of other groups think about the relationship between futures work and policy development in more sophisticated ways, too. I’m going to talk about some of the work these groups are doing in the real world in later newsletters. For now, I’m focusing on the underlying orientation to the future generally found across public policy, and the gradual spread of a new, more encouraging approach.

✻

In the UK civil service there is a collection of disparate teams brought together under the umbrella of the ‘Future Policy Network’. It’s hard, at first, to see what they all have in common, beyond a capacity to irritate more traditionally-minded parts of the civil service: behavioural insights sit next to technology evangelism, social investment, data policy, design thinking, foresight, and more established bridges between academia (’science’) and policy groups. Taken as a whole, despite the differences between them, I suppose the group tells a useful story about how government tries to do new things. And all of them are inheritors of the kind of orientation that Jenny Andersson describes in her 2018 book, The Future of the World, a planning rationality that constructs the future, rather than the present, as a space of action and influence. Indeed, in keeping with her account of the competition between different schools of what she calls ‘futurism’, many of the groups in the Future Policy Network represent modes of thinking about the future that can often be in tension with each other, or at least are based on widely-differing ways of understanding the world.

The Future boardgame, ‘a game of strategy, influence and chance’, designed for the Kaiser Aluminum Corp in 1966 by Hans Goldschmidt, T. J. Gordon and Olaf Helmer (picture by Charles Picard)

But at their root they share an interest in managing ideas about the future in a way that extends the horizon of the interests of the present: they all, in their own ways, propose possible future circumstances as ways of shaping and influencing action that is in our interests, now, and that maintains the structures and relationships that make up our present society. This is not in itself a bad thing. Two recent pieces of work, the UK2070 Commission recommending long-term policy actions to address spatial inequalities and promote regional devolution, and the twin British Academy reports on the post-covid future of British society (commissioned by the Government Office for Science, a member of the Future Policy Network), are both important pieces of public policy futures work, genuinely helpful to policy teams working out how best to serve society. They don’t use any particular foresight or futures tools, but in drawing together academic evidence to support descriptions of possible future circumstances they make the case for particular policy actions now. The people who produced this work are at one remove from the futurists Andersson describes, though they are also working to create images of the future to shape society over the long-term, and in their recommended policy actions they show they are inheritors of the technocratic forms of governance the Cold War struggle for the future ushered in.

✻

Andersson describes an orientation to the future that, she suggests, gradually became less visible over the post-war period, as futures work became more technocratic and more concerned with using uncertainty and prediction to perpetuate the structures of the present, one that saw the future as “a field of resistance, love and imagination” (Andersson 2018:225). Adam and Groves, in their foundational 2007 book Future Matters, set out the case for thinking about the future, not as open and abstract, but embedded in a real set of human relations with us: adopting this orientation means relating to the future with care. Their argument is powerful, and also quite abstract, and uncompromising in its characterisation of the kinds of futures governments work with as damaging and inhumane.

What are you supposed to do with this, if you work in policy? People in policy teams also care about the future, and don’t want to be part of something damaging. How do you make use of this idea of care in policy futures?

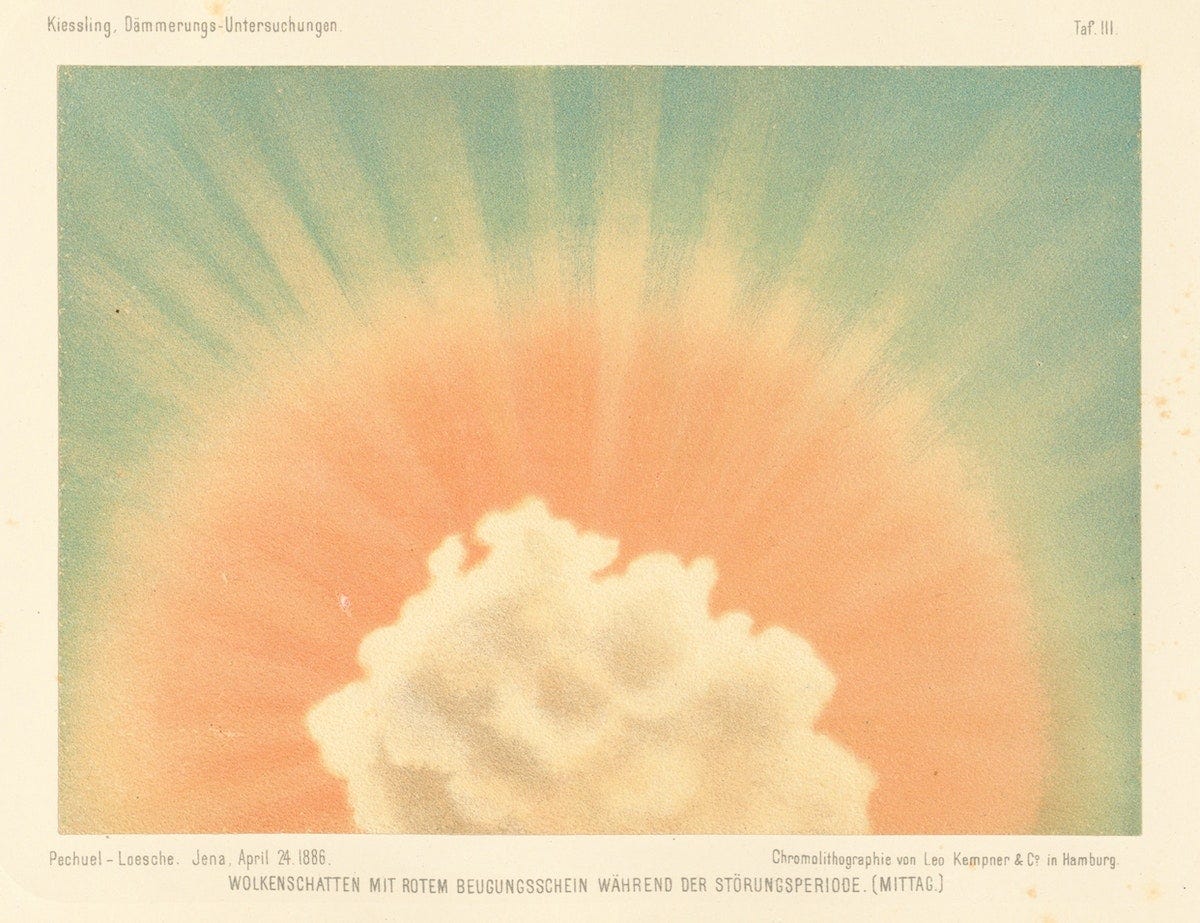

Cloud Shadow With Red Diffusion Light During the Disturbance Period. (Midday) — Jena, April 24th 1884, Eduard Pechuël-Loesche

Perhaps one answer lies in the recent turn to future generations. People generally approve of taking future generations into account, and are not as self-interested as policy makers have generally assumed (suggest Hilary Graham and colleagues in a 2017 paper). The rights of people in the future, and the onus on us not to limit their choices unduly, are ideas that have made their way from academia into recent pop futures books like Roman Krznaric’s Good Ancestor and into policy design. The School of International Futures, a non-profit foresight group, have in the last few years developed a Framework for Intergenerational Fairness, designed to help governments evaluate the impact of their policies across generations, and set up a network intended to ensure younger generations have a voice in developing national strategy. In Japan, Tatsuyoshi Saijo and Keishiro Hara have developed the Future Design process, in which participants in the policy design process take on the role of speaking for future generations. Other groups are concerned more directly with the existential risks faced by future generations. Based in the Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER), Jones et al (2018) highlight the intergenerational unfairness of our technological development creating such risks, and survey a number of policy bodies set up around the world to promote the interests of future generations in policy making. They call for a UK All-Party Parliamentary Group for Future Generations: this was set up in 2017 with the support of CSER.

The APPG is supporting Lord Bird’s Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill, itself modelled on the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act that created a Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, tasked with being a “guardian for future generations”. The Welsh example has been hailed around the world as a model and inspiration, particularly for its attempt to give as much statutory force to its policy aims as practicable. Jane Davidson, who as Minister for Environment, Sustainability and Housing in Wales originally proposed the legislation, has an account of the long journey towards this becoming law in her book, #futuregen. It’s an illuminating account of many small victories and necessary compromises: if you’re interested in how policy gets made, it’s a great read.

The Senedd’s Public Accounts Committee recently published a report on the Commissioner’s work, Delivering for Future Generations: The story so far. This is a more sobering read. Putting the Act into practice has been difficult. They identify a need to change culture and expectations in government, and principally to change the funding mechanisms supporting it, which at present are not joined-up, often subject to last-minute change, and insufficient. None of which is a surprise: in a way, the real surprise is that the government in Wales appears so committed to making the Act work, in the face of all the many challenges it presents.

✻

In practice, this future generations approach can look very similar to traditional foresight, in terms of the policy recommendations that come out of it, and the social futures it tends to promote (more sustainable, more equitable). But it’s a fundamentally different future orientation for policy makers. In considering future generations alongside present generations we do two things. We make a shift from seeing the future as a resource to exploit or colonise, to understanding that we have an ethical responsibility to it and the people there. And we decentre our present, making our thinking less concerned with projecting forward from now, and more concerned with imagining multiple presents, ours and our descendants’.

Page from the friendship book of Anne Wagner, a scrapbook of contributions from friends and family created between 1795-1834: a kind of proto-Instagram

This is one way of relating to the future with care. Ian Scoones and Andy Stirling also talk about care and the future in policy: introducing their collection The Politics of Uncertainty, they suggest that the technocratic approach to the future Andersson describes is insufficient as a basis for governance, given the central place of uncertainty in contemporary society, and that, rather than attempting to use technologies of prediction to chase an illusion of control, we need to develop a politics of care that is able to move away from brittle, market-led notions of responsibility and citizenship, towards a more convivial, deliberative, inclusive way of facing uncertainty, and recognising the hope and possibility it contains.

This is where heritage can make a contribution, too. This relation of care towards the future is what underpins the whole notion of heritage, which tends also to frame its responsibilities towards the future in generational terms. Thinking about the future through heritage prompts us to think about previous generations and what they have to contribute to policy. It might seem counter-intuitive, in this context, to insist on thinking about previous generations (haven’t they had their say? Aren’t they the ones running the department?) but the point here is to think intergenerationally in all directions. Loading expectations about the future onto the shoulders of the next generation can lead to the kind of thinking that says ‘children are our future’ without thinking about what these children might need from us to build a future, or how they might benefit from a focus on their lived present rather than our imagined future (a point Sarah May makes in her contribution to Cultural Heritage and the Future, and which Nick Lee has explored in his work). And thinking generationally at all means we remain committed to a heteronormative and patriarchial idea of what it means to reproduce ourselves into the future, something Carmen Dell’Aversano and Florian Mussgnug challenge us to consider. Perhaps one task for those of use working in heritage is to recognise other forms of family life which might offer a different way of relating to those not yet present.

So that’s our challenge: how can we draw on heritage ideas to help policy teams put a politics of care into practice?

Links

On the challenges facing policy groups who are the first to try new things: detailed and informed exploration of ‘vanguard projects’ from Alex Roberts at the OECD’s public sector innovation team ❡ Mentioned by Monika Stobiecka in our recent conference, the Slow Looking app will help you really *look* at museum and gallery exhibits ❡ What Does It Mean To Buy A Gif, a measured exploration of the NFT madness ❡ Read-along children’s guide to 2001: A Space Odyssey ❡ Promises, from Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders & The London Symphony Orchestra: beautiful music.

Colophon

Thanks for reading! If you're interested in the programme, there's more information on how to apply here: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/heritage/study/heritage-evidence-foresight-and-policy-msc.